In today’s world, learning increasingly relies on multimedia formats, blending visuals, text, and audio to convey information. Yet, not all multimedia content is created equal—some designs enhance understanding, while others overwhelm learners. Richard Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML) provides a roadmap for creating effective educational materials by tapping into how the human brain processes information. At its heart lies the Dual-Channel Theory, which highlights the need to consider verbal and visual communication in learning design.

The Dual-Channel Theory Explained

Mayer’s Dual-Channel Theory posits that humans process information through two separate cognitive channels:

- The Visual Channel: Processes images, diagrams, animations, and other visual representations.

- The Verbal Channel: Handles spoken words, written text, or narration.

These channels work independently yet complement each other. For example, when we watch a video with narration explaining a diagram, the visual and verbal channels collaborate to build a comprehensive understanding. However, both channels have limited capacity, which leads us to the next challenge: avoiding overload.

Cognitive Overload and Its Impact

Each channel can only handle a finite amount of information at once. Overloading either channel diminishes the brain’s ability to process and retain content. This is a common pitfall in poorly designed multimedia—think of a slide packed with detailed text alongside an intricate diagram while the presenter speaks rapidly. Instead of reinforcing the message, such an approach divides attention and overwhelms the learner.

Mayer suggests using multimedia to complement the channels to mitigate cognitive overload rather than compete for their resources.

Optimizing Dual-Channel Processing

The effectiveness of multimedia hinges on properly balancing input across both channels. Here are some evidence-based strategies derived from Mayer’s research:

- Combine Visuals and Narration

Use narrated explanations rather than on-screen text to accompany visuals. For example, a science video showing an animation of a chemical reaction should feature a spoken explanation rather than written captions. This prevents the learner from overloading their visual channel with animation and text. - Avoid Redundancy

Redundant information—like displaying the exact text being spoken—can unnecessarily split attention. Mayer’s Redundancy Principle advises against repeating identical content across channels. Instead, use complementary inputs: visuals to explain structure and narration to provide context. - Segment Information

Break complex topics into smaller, digestible chunks. By segmenting content, learners can focus on one part of the material before moving on to the next, reducing cognitive load. For example, e-learning modules often incorporate short, focused lessons rather than lengthy presentations.

Real-World Applications

Mayer’s principles are widely applied in educational technology, corporate training, legal contexts, and instructional design:

- E-Learning Platforms: Tools like Coursera and Khan Academy design courses that effectively integrate visuals and narration, using animations and videos to simplify complex concepts.

- Corporate Training: Training programs often use short video clips with clear diagrams and concise voiceovers to explain procedures or introduce new tools.

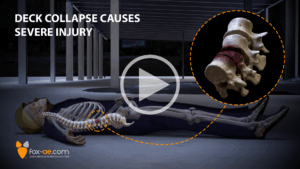

- Legal Animation in Courtrooms: Courtroom presentations increasingly rely on legal animations to clarify complex cases. For instance, a 3D animation might visually reconstruct a car accident to help jurors understand the sequence of events. These animations, paired with verbal narration by legal experts, utilize the Dual-Channel Theory to make technical details accessible and persuasive to a lay audience. By presenting information in both visual and verbal forms, legal teams ensure that jurors can process and retain crucial details without being overwhelmed.

- Classroom Settings: Teachers can use tools like PowerPoint or Prezi to combine images and spoken words rather than cluttering slides with dense text.

Conclusion

The Dual-Channel Theory underscores a crucial truth: effective learning hinges on how well we balance visual and verbal input. Educators, content creators, and even legal professionals can maximize engagement and retention by designing multimedia materials that align with how our brains naturally process information. Whether you’re creating an e-learning course, a corporate training module, or a courtroom presentation, applying these principles ensures that your audience doesn’t just see or hear your content—they truly understand it.

Mayer’s insights remind us that the art of teaching in the multimedia age is as much about what you leave out as what you put in. When we understand the science of how people learn, we can create materials that educate, inspire, and empower.

Mayer, R. E. (2020). Multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.