The Role of Modality and Contiguity in Legal Animation

In complex legal cases, especially those involving accidents or technical details, conveying intricate information to a jury is a formidable challenge. Legal animation—3D visual reconstructions of events—has become an effective tool in aiding comprehension. But not all animations are created equal. Legal professionals must consider cognitive principles that guide multimedia learning to maximize their impact. Two principles from Cognitive Principles of Multimedia Learning by Richard E. Mayer and Roxana Moreno—the Modality Principle and the Contiguity Principle—are crucial in shaping how animations should be designed for legal presentations.

The Modality Principle in Legal Animation

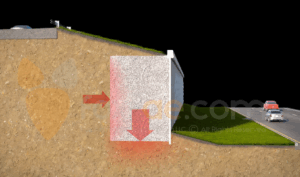

The Modality Principle posits that people process visual and verbal information through separate cognitive channels—the visual channel for images and the auditory channel for spoken words. Cognitive overload occurs when both types of information are presented simultaneously but in the same channel (e.g., with on-screen text). This principle is applied in legal animation by replacing on-screen text with narration. For example, in a car accident case, an animation that visually shows the sequence of events should be accompanied by a spoken narrative that explains what is happening rather than cluttering the screen with written text.

Benefits:

- Jurors do not need to divide their attention between interpreting images and reading text, which can improve understanding and retention.

- Narration delivers the content more fluidly, mimicking how jurors would be guided by an expert explaining a sequence in real-time.

Example: In a personal injury case, a narrated animation could show how an accident occurred at an intersection. The narration would explain each step in the process—such as the speed of the vehicles, the angle of impact, and the response times—without overwhelming the viewer with dense text.

The Contiguity Principle in Legal Animation

The Contiguity Principle has two components: spatial contiguity and temporal contiguity. According to this principle, information should be presented to minimize the cognitive load of linking visual and verbal elements.

- Spatial Contiguity: This refers to the proximity of related text and visuals. In legal animation, this principle can be applied by ensuring that any text or labels related to a specific visual are placed near the relevant part of the animation. For instance, when showing the interior of a vehicle in an accident reconstruction, labels identifying critical features like “driver seat” or “brake pedal” should be displayed directly next to the corresponding objects within the animation.

- Temporal Contiguity: This involves synchronizing visuals and narration to co-occur. In legal animations, narration should accompany the visual action in real time. For example, suppose a reconstruction shows a vehicle swerving to avoid a pedestrian. In that case, the narration should describe the event as it unfolds on the screen rather than explaining it before or after the animation.

Benefits:

- Reduces the mental effort required to integrate verbal and visual information.

- Enhances the clarity of the message by presenting information in a logical and coherent flow.

Example: In a legal case involving a medical procedure, the animation of the procedure should show the steps as they are explained in the accompanying narration, with labels beside the appropriate body parts or instruments to avoid confusion.

Conclusion

Legal animation is an invaluable tool in clarifying complex evidence in court. By applying the Modality Principle and Contiguity Principle, legal professionals can create more effective, engaging animations that improve juror comprehension and retention. When both principles are used together, they ensure that the information presented is easy to follow, accessible, and memorable, making legal arguments clearer and more persuasive.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. E. (2000). Cognitive principles of multimedia learning: The role of modality and contiguity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 117–125.